What are anaesthesia and analgesia in veterinary medicine?

Anaesthesia and analgesia are integral parts of modern veterinary care. They enable safe and pain-free performance of not only surgical procedures but also diagnostic interventions. Proper anaesthetic management requires knowledge, experience, high-quality equipment, and close monitoring. For us, anaesthesia and analgesia represent essential tools to ensure maximum comfort and safety for our patients.

General anaesthesia is a controlled, pharmacologically induced state of unconsciousness and insensitivity to pain, which allows for the performance of more extensive surgical (or dental) procedures.

Local anaesthesia is used to numb a specific part of the body. In veterinary medicine, it is often used as an adjunct to general anaesthesia.

Analgesia refers to pain relief. It should be part of every general anaesthesia protocol and is also used independently—for example, after surgery or in acute pain situations.

A brief history

Although modern anaesthesiology is a relatively young field—having formally developed over the past 160 years—the effort to alleviate pain reaches far back into human history. Records from ancient Egypt already mention the use of natural substances for pain relief. In the modern era, the introduction of ether and chloroform in the 19th century played a crucial role, making the first truly pain-free surgeries possible. Today, anaesthesia is a precisely controlled and safe process that continues to evolve.

"Anaesthesia is not inherently safe — the safety lies with the anaesthesiologist."

Types of anaesthesia

Anaesthesia is classified based on the method of administration and combination of techniques:

TIVA – Total Intravenous Anaesthesia

Inhalation anaesthesia

Balanced anaesthesia – combination of intravenous and inhalation anaesthesia

Combined anaesthesia – intravenous and inhalation anaesthesia + regional nerve blocks (local anaesthesia)

TIVA – Total Intravenous Anaesthesia

The patient has an intravenous access secured, and all anaesthetic agents are administered exclusively via the intravenous route, typically using drugs such as propofol. TIVA is suitable for shorter procedures or for patients in whom inhalation anaesthetics (e.g. isoflurane) are contraindicated — for instance, in cases of malignant hyperthermia. After administration of the intravenous anaesthetic, the patient can be safely intubated and connected to an anaesthesia machine supplying only a mixture of oxygen and air (without any inhalation agent such as sevoflurane).

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is a rare, genetically determined reaction to certain anaesthetic agents (primarily inhalational), which can lead to a rapid rise in body temperature, muscle rigidity, and metabolic collapse.

MH most commonly occurs in certain dog breeds, including the Labrador Retriever, Pointer, Greyhound, or Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. These patients require carefully managed TIVA protocols without the use of high-risk agents.

Inhalation anaesthesia

The patient has intravenous access secured, but no intravenous anaesthetics (e.g. propofol) are administered. Instead, the patient inhales an anaesthetic agent (e.g. sevoflurane) through a veterinary anaesthesia mask. However, the airways are not secured with an endotracheal tube.

In veterinary medicine, animals are generally not anaesthetised using inhalation gases alone via a mask without prior administration of intravenous agents. Unlike human medicine (e.g. in paediatrics), this method is highly stressful, unsafe, and difficult to control for animals (with the exception of small mammals). Animals do not understand what is happening to them, and contact with a mask delivering an unfamiliar gas is perceived as a threat. Most animals resist, struggle, become stressed or panic, increasing the risk of injury to both the animal and the staff. Moreover, the onset of action for inhalation anaesthetics delivered by mask is slower and less predictable. This results in a prolonged transitional phase between consciousness and unconsciousness, which is undesirable. Without prior sedation using intravenous anaesthesia, it is also unsafe to secure the airway (via intubation) or to connect the patient to an anaesthesia machine.

Balanced anaesthesia (intravenous + inhalational)

This approach combines the two main types of anaesthesia—intravenous and inhalational. The patient has secured intravenous access. First, an intravenous anaesthetic (most commonly propofol) is administered, and only then is the patient intubated and connected to inhalational anaesthesia.

This method is primarily used for surgical procedures and painless dental interventions. It combines the rapid onset of intravenous agents (such as propofol) with the ability to maintain anaesthesia over time using precisely dosed inhalational agents (such as isoflurane). It allows for smooth induction and awakening, providing a gentle and well-tolerated course for the patient.

Combined anaesthesia (intravenous + inhalational + regional)

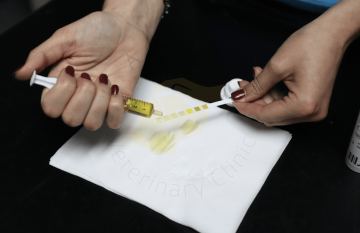

When regional (local) anaesthesia is added to balanced anaesthesia, the result is what's known as combined anaesthesia. The patient has secured intravenous access. First, an intravenous anaesthetic (most commonly propofol) is administered, followed by intubation and connection to inhalational anaesthesia. A regional anaesthetic is then applied, providing excellent analgesia precisely at the site where it is most needed. This involves local nerve or nerve plexus block using a local anaesthetic (e.g. levobupivacaine).

A typical example is dental treatment, where levobupivacaine is routinely used to block the facial nerves.

Balanced and combined anesthesia are considered state-of-the-art approaches and, together with multimodal analgesia, represent the gold standard of anesthetic care at our clinic.

What is analgosedation?

Analgosedation is a state in which the patient is sedated and simultaneously relieved of pain (analgesia). It is not full anaesthesia – the patient may remain conscious or in a light sleep but does not feel pain and remains calm.

A combination of sedatives and analgesics is used, allowing for short or less painful procedures without the need for deep anaesthesia. The advantages include gentleness, shorter recovery time, and fewer side effects.

When is Analgosedation used in animals?

X-ray examinations (e.g., hips, spine)

Short diagnostic procedures (e.g., blood samples, punctures)

Treatment of minor injuries

Removal of stitches, ticks, etc.

Endoscopy, sonding

Certain dental procedures (e.g., braces replacement)

However, analgosedation does not provide airway management (intubation) and is not suitable for painful or longer surgical procedures.

Important parts of anesthesia

Securing intravenous access

Every patient must have intravenous access secured before general anaesthesia – an intravenous catheter in the paw. This access is essential for administering premedication, anaesthetics, and infusion therapy. In our practice, we most commonly choose intramuscular premedication – this calms the animal, reduces stress, and allows the catheter to be safely and painlessly inserted. However, note that this is not intramuscular anaesthesia, which has become obsolete in veterinary medicine. The rule is: "No vein, no anaesthesia."

Intubation

Insertion of the Endotracheal Tube (Intubation) is performed only after the administration of intravenous anaesthetics! Without this step, it is not possible to safely and painlessly insert the endotracheal tube into the trachea. In our practice, we also routinely use a local anaesthetic spray before intubation, making the procedure even more comfortable for the animal. Once the intravenous anaesthetics are administered and the airway is secured with the endotracheal tube, we can safely connect the patient to inhalational anaesthesia through the anaesthesia machine (balanced anaesthesia).

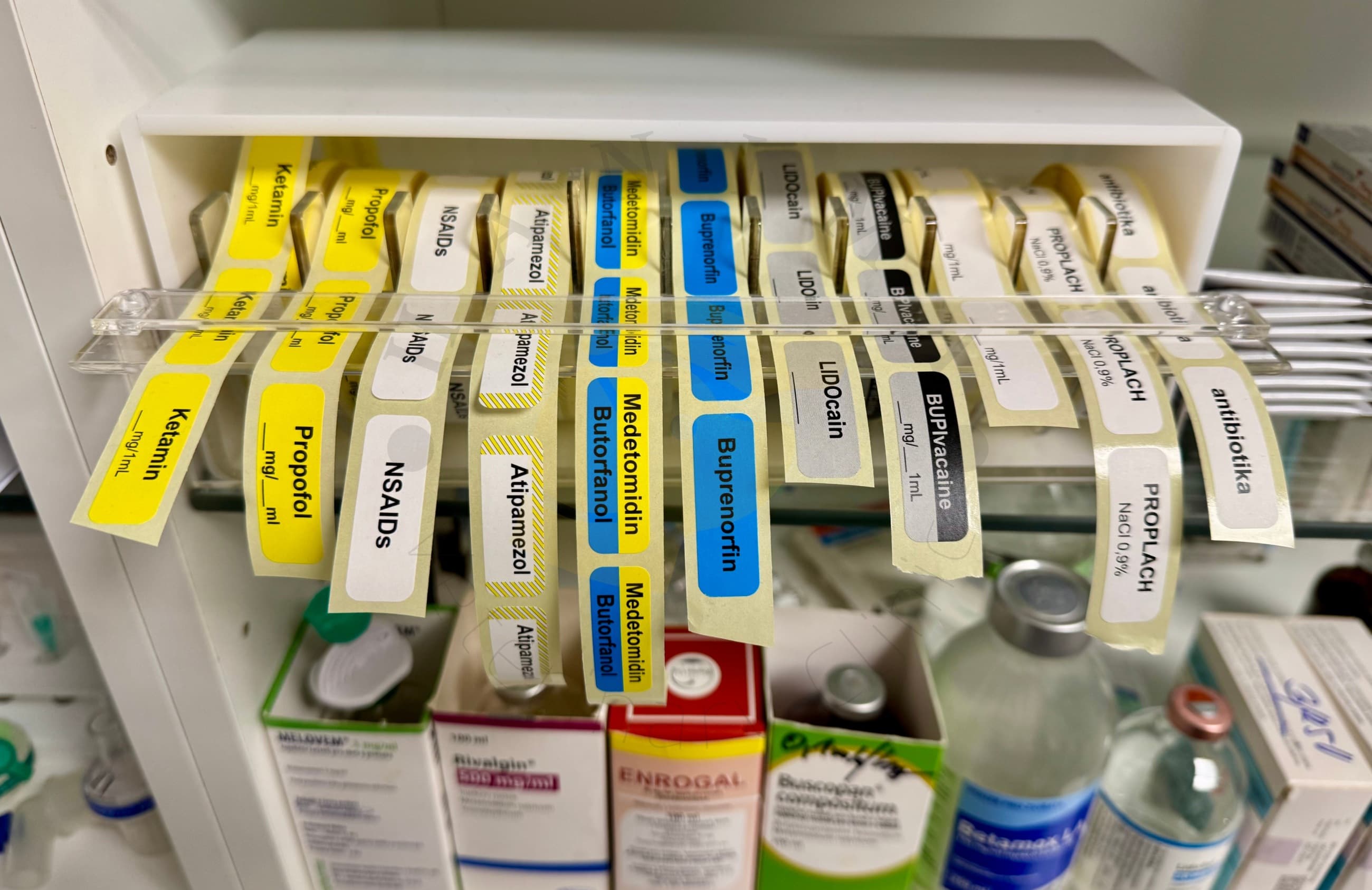

Multimodal analgesia

Multimodal analgesia is the most modern and highly effective approach to pain management, combining several different types of medications and techniques simultaneously. Each of these agents targets a different pain mechanism, allowing for a stronger effect with smaller doses of each drug. Anaesthesia does not automatically mean analgesia! The goal is not only to "sedate" the patient, but primarily to relieve pain in the gentlest way possible.

Patient monitoring

Monitoring throughout the procedure is an integral part of anaesthesia. It is crucial for the safety of the anaesthetic process.

Each patient is connected to a life function monitor and is attended by a dedicated anaesthesiologist who monitors:

ECG – heart activity

Oxygen saturation (pulse oximeter)

Blood pressure

Body temperature

Pulse and heart rate

Respiratory rate

Capnography – the level of carbon dioxide in exhaled air

Hydration

Depth of anaesthesia, and more.

Thermal comfort and infusion therapy

During the procedure, we ensure the maintenance of body temperature using:

heated pads and socks

thermal blankets

infusions heated to physiological temperature

Hypothermia increases the risk of complications, prolongs recovery, and worsens overall convalescence.

Infusion therapy is an integral part of every anesthesia. It helps maintain blood pressure, supports organ perfusion, aids in the elimination of anesthetics, and stabilizes the internal environment of the patient.

Mechanical ventilation (MV)

MV is essential for patients who stop breathing spontaneously or during procedures where complete control over breathing is required. The machine regulates the respiratory rate, tidal volume, airway pressure, and the composition of the oxygen and anaesthetic gas mixture.

How do we do ANESTHESIA at HANIMA?

- equipment, types of anesthesia, analgesia and safety standards -

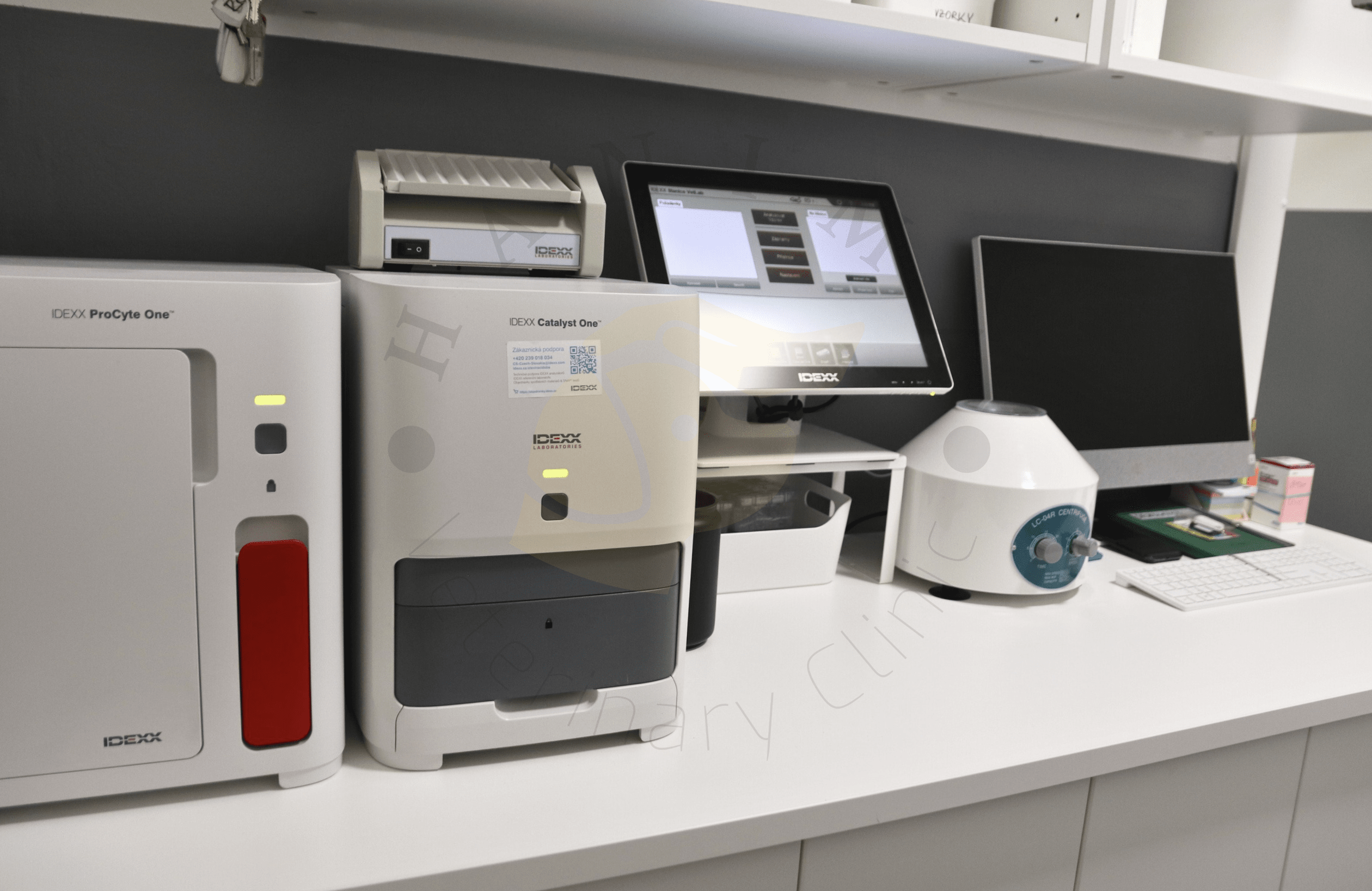

Equipment

In our facility, we use the most modern veterinary anesthesia devices, specifically the Mindray VETA 5 PRO with an integrated ventilator (supporting both pressure and volume ventilation, with a wide range of ventilation modes) and the Mindray 3S. These devices allow us to safely anesthetize patients weighing from 500 g to 60 kg. For different sizes and needs of patients, we have a variety of anesthesia circuits, including the Mapleson F or C circuits and a neonatal closed circuit, which are primarily used for the smallest patients, and a coaxial breathing circuit for patients weighing from 8 kg.

Our anesthesia machines are also equipped with high-quality Mindray uMEC 12Vet monitors, which track capnometry values, oxygen saturation with a pulse oximeter, blood pressure with BERRY and Mindray cuffs, ECG, and rectal temperature. This way, we maintain control over all critical patient health parameters during anesthesia.

To maintain thermal comfort, we use the advanced Longshore air warming system for effective patient warming, Sigmed heated pads with thermostats, warming socks, blankets, and thermal blankets, ensuring optimal temperature throughout the procedure.

Infusion therapy during and after anesthesia is managed with the Lexison PRIP-E400V VET veterinary infusion pump, which allows us precise fluid dosing.

For any potential complications, we have a fully equipped "crash trolley" – an anesthesiology cart with resuscitation medications and equipment for immediate intervention in emergency situations.

Types of anesthesia and analgesia

Before general anesthesia, each patient receives intramuscular premedication to alleviate fear and anxiety, providing mild sedation. Following this, venous access (an intravenous catheter) is secured, and the type of anesthesia is selected based on the procedure. At HANIMA Veterinary Clinic, we most commonly use supplemented anesthesia (intravenous + inhalation) and combined anesthesia (intravenous + inhalation + local). We use combined anesthesia for every dental patient! Less frequently, we apply analgesosedation (e.g., for hip X-rays, ultrasound in patients that cannot be safely treated, orthodontic adjustments, and others) and TIVA (only for patients with malignant hyperthermia).

For every patient, we always employ multimodal analgesia. Each patient is thoroughly monitored, kept warm, receives infusions, and is under the constant supervision of an anesthesiologist throughout the procedure. For more complex cases (elderly and polymorbid patients, cardiac patients, long and complex surgeries), a human anesthesiologist, MUDr. Anna Hanzel from the Department of Anesthesiology, Resuscitation, and Intensive Care Medicine at the 2nd Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, and FN Motol, is present by prior arrangement.

Safety Standards

Our veterinary nurses undergo regular retraining in the management and supervision of anesthesia, under the guidance of a human anesthesiologist.

During each procedure, an anesthesiological protocol is maintained, recording the entire course, drug doses, times, and monitoring values.

We are equipped with a "crash trolley" – an anesthesiological cart with a complete set of resuscitation drugs and equipment for any complications.

After every procedure, the patient remains under supervision until fully conscious and able to move. They always leave on their own feet and are never sent out sleeping. A mild "drunken" walk shortly after waking is common and not a cause for concern. In the first 24 hours post-procedure, increased fatigue and drowsiness are to be expected.

Final Note

We often hear that inhalation anesthesia is “safer” or “gentler” than injectable anesthesia (known as TIVA), and that TIVA is outdated or less suitable. However, such simplified claims do not reflect the reality of modern veterinary medicine.

In veterinary practice—excluding some small mammal species—pure inhalation anesthesia is rarely used. The term “inhalation anesthesia” is more accurately a simplified label for balanced (intravenous + inhalation) or combined anesthesia (intravenous + inhalation + regional). In essence, it's more a matter of terminology—but it's crucial to understand what each term truly means.

Each type of anesthesia has its own specific benefits and clear indications. None should be dismissed categorically. On the contrary, well-managed TIVA can, in certain cases, be not only entirely appropriate, but the most suitable option. In fact, for some patients—such as those with malignant hyperthermia—TIVA is the only safe alternative.

Ultimately, the safest form of anesthesia is the one that the anesthesiologist is well-trained in and can tailor to the individual needs of the patient. Today’s advanced knowledge, equipment, and monitoring technologies allow us to perform anesthesia with a high degree of safety. Still, the most important factor remains an experienced and skilled anesthesiologist, not the technique alone.

Truly gentle and responsible anesthesia means that the patient is provided with maximum relief from pain, stress, and discomfort—regardless of the method used.

Anesthesia is not simply “putting an animal to sleep”—it is a distinct field of medicine requiring deep expertise, precision, and continuous learning. Safe and high-quality anesthesia does not happen by chance; it is the result of training, teamwork, and genuine respect for the patient.